Loan Le and Maitria Moua’s article, “Civilian Oversight and Developments in Less Lethal Technologies: Weighing Risks and Prioritizing Accountability in Domestic Law Enforcement,” has now been published.

Here are a few excerpts:

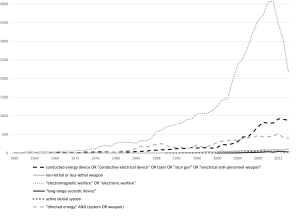

There is growing interest in the domain of “electromagnetic warfare” or “electronic warfare” (see Figure 1), which has contributed to developments in a category of weapons that rely on pain compliance and directed energy or directed sound.

Figure 1. Comparing Growth Counts in Articles from Google Scholar for Less Lethal Technologies

Eugene O’Donnell, Professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, noted: “The one truly indispensable military technology the police should hurry into service is reliable nonlethal weaponry–like the Pentagon’s so-called pain ray. It is hard to believe that in the year 2014, police officers have to take lives just to enforce the law” (O’Donnell 2014). “He adds that training and ‘robust oversight’ are central to the judicious use of emerging sophisticated weaponries” (Le and Moua 2015: 104-105).

“While the use of less lethal weapons may have advantages in policing, there are caveats to consider by all stakeholders moving forward. These new weapons pose challenges to the police oversight community because those that are based on the electromagnetic spectrum, such as the ADS (Active Denial System) are silent and invisible to the naked eye. Yet they rely on pain compliance…Oversight professionals may find it difficult to monitor and audit how frequently, at what intensity, and at which targets these weapons are aimed and discharged; therefore, the features of these weapons call attention to substantial risk for undetected abuse” (p. 109).

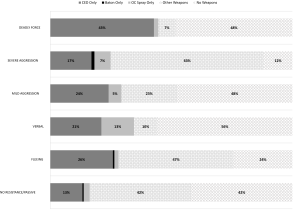

“Contrary to guidelines for their utilization in the field, we found that officers deploy CEDs in a substantial number of cases involving suspects who do not comprise immediate dangers to public safety, including those who offer no resistance and those who are only passively resistant [13% of these cases, a conservative estimate] (p. 140, see Footnote 1 below for methodology). On the other hand, in a multivariate analysis testing whether suspects who are perceived as violent will be more likely to be subjected to CED deployment, all else equal, Le and Moua found that indeed the RRR of an officer deploying a CED over no weapon for a suspect who is perceived as violent is 2.64 (p<.001) (p.137).

Figure 2. Suspect Behavior by Officer Weapon Used, Among CED-Yes Agencies

As we move forward, CEDs will number one among a class of energy weapons that are able to be administered from a distance without wires that need to attach to a target’s skin. These weapons, because they are invisible to the naked eye, are rife for abuse of power without detection” (p.140). “We must take proactive action in order to enhance public safety and prevent abuses of power that detract from the work of good officers who are on the job every day” (p.144).

We list five recommendations (p. 141-142):

1 – Oversight practitioners should gain experience using public records to assess what weapons agencies are deploying, where these weapons fall on the use of force continuum and monitor violations.

2 – Oversight practitioners should gain access to training in methods of new detection and forensics that keep pace with developing technologies.

3 – Less lethal equipment should be designed such that data for each discharge are automatically recorded and retained for statistical analysis.

4 – Oversight practitioners should seek additional auditing powers, such as randomized audits with lie detector tests for stakeholders (including informants and officers) over the course of long-running investigations to make sure that resources are not being misused.

5 – Agency officials should strengthen whistleblower protections.

With permission from the publisher, a copy of the article will be made available on IGGI’s website. Check back for an update.

Images

Featured image credit: Image is from the cover of the Seattle Journal for Social Justice, Volume 14, Issue 1. Cover Art by Joshua Alonzo Angeles. The image underscores discomfort between police-civilian interactions, as demonstrated by sweat dripping from one of the hands. Is this an exaggeration or is there merit to the sentiment as depicted? IGGI’s article underscores through a study on tasers that even interactions with passive suspects, use of force is applied in enough instances to be concerning. IGGI concludes its study with recommendations that we should consider now and in the future.

Slider link photo credit: csmyts 130115-A-6855S-019 via photopin (license)

References

Le, Loan & Moua, Maitria (2015). “Civilian Oversight and Developments in Less Lethal Technologies: Weighing Risks and Prioritizing Accountability in Domestic Law Enforcement.” Seattle Journal for Social Justice 14(1): 101-144.

O, Donnell, Eugene (2014). Military Training and Technology May Actually Cut Risk. New York Times (Aug. 28, 2014).

Footnotes

(1) Estimates are segregated by CED-Yes versus CED-No agency types, i.e., whether a given police agency officially adopted CEDs in its use-of-force policy. It is important to note that a non-negligible number of tasers were deployed during the pre- and post-CED adoption periods across agency types. Our comparisons of officer weapons deployed by suspect behaviors are intended to be comprehensive and use all available data. Note that for the no resistant behavior/passive suspects category, no CEDs were fired during the pre-period, whereas there were 159 reports of CED utilization during the post period. Therefore, because the evaluation is not restricted to the post-adoption period, estimates provided for CED deployment with no resistant behavior/passive suspects are conservative. Differences in reporting behaviors may have emerged during the pre- versus post- periods. For example, once agencies adopted tasers in their use-of-force policies, officials may have been provided with enhanced training for CED deployment and use-of-force reporting. For the purposes of this article, conservative estimates are sufficient to establish that tasers were deployed (improperly) in a substantial number of cases with suspects who demonstrated no resistant behavior or who were otherwise passive. Among CED-Yes agencies, tasers were used more commonly with suspects who displayed some level of resistance, with for example 12 firings during the pre-period and 30 firings during the post period for the mildly aggressive suspects category (counts were 25 and 184, respectively, for the severe aggression suspects category). Further study is needed in order to determine the net effect of official CED agency adoption on patterns of taser deployment and reporting.