Critical thinking on controversial issues is hard, and learning good thinking habits makes each citizen psychologically healthy. Given the plethora of unfiltered information available online and concerns about declines in hard-hitting investigative journalism, how can the average citizen stay informed about issues they care about? In this post, I underscore the work of Anderson and Krathwohl (2001) on critical thinking.

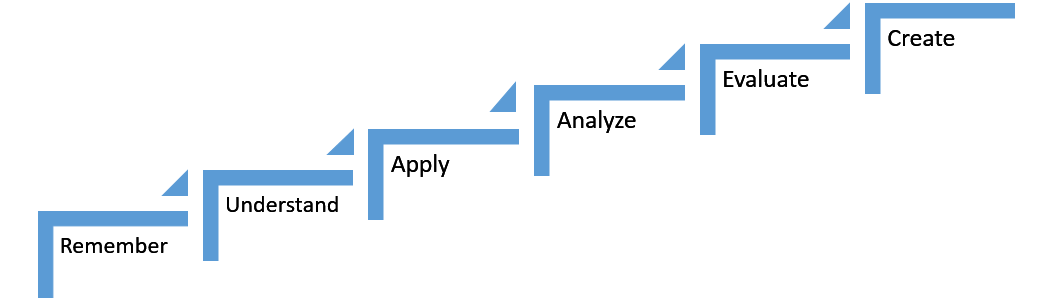

Anderson & Krathwohl’s (2000) stages of critical thinking:

Stage 1: Learners need to remember or retrieve key information, definitions, facts etc. How can an individual even begin thinking critically on controversial issues without the necessary knowledge? If he or she lacks information, then the learner should seek it out from credible sources before forming an opinion. This may involve obtaining records from a government agency directly through public records requests.

Stage 2: Learners need to understand what the information means by being able to classify, summarize, compare and interpret the data.

Stage 3: Learners need to apply their knowledge or put it to use, such as by implementing it in presentations or in simulations or in real-life situations.

Stage 4: Learners need to analyze the information by being able to split components and assess how the parts relate to one another, such as by designing experiments.

Stage 5: Learners need to properly evaluate or judge information by making value assessments or providing feedback based on reliable standards for evidence.

Stage 6: Learners need to create by putting the information together and reorganizing them into a new, coherent structure that requires synthesis into a new product.

Each of these stages of critical thinking requires an active learning posture. Stage 6 is the most challenging level of critical thinking and it may take years of practice before this level of mental processing is achieved.

The reality is that consumers need to fine-tune their critical thinking skills, which includes their ability to acquire and digest information.

After all, how much attention a problem is being given influences consumer perceptions of its importance and yet respected journalists from various outlets have reported on diminishing press freedoms:

Glenn Greenwald from The Guardian observed that the “administration is intensely and, in many respects, unprecedentedly hostile toward the news-gathering process.”[1] Former general counsel for the New York Times, James Goodale, made similar observations regarding “press freedom.”[2] A report from the Committee to Protect Journalists quotes New York Times reporters Scott Shane and David Sanger as “scared to death” and as having observed that “this is the most closed, control freak administration I’ve ever covered,” respectively.[3]

Given that these respected media reporters and organizations are reporting that their press freedoms have been sharply curtailed, we must teach our students to think critically and be more attentive and to search more broadly for their news instead of relying on a few sources. Based on my experience with students at UCLA, I (Dr. Le) observed that students do not know enough about the sharp growth in what the scholarly literature calls the “Imperial Presidency” (Schlesinger 1973) and fundamental shifts in the balance of power between Congress and the President. Our students may have heard of the Patriot Act, but they know little about the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) or the Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF). They do not know that some states (e.g., Michigan) were particularly concerned about the indefinite detention of American citizens without due process and that these states pushed back against the federal government by passing state legislation intended to preclude its enforcement. Dominant sources for news such as the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle and the Washington Post did not provide much if any coverage of these developments in power struggles that redefine our constitutional system of checks and balances as provided by the United States’ Constitution. An exception is Forbes,[4] which reported on Michigan’s attempts to pass a bill barring state agents and law enforcement from assisting the federal government with the indefinite detention of citizens. The Washington Times reported that Governor Rick Snyder of Michigan signed Senate Bill No. 94, which seeks to nullify section 1021 of the 2012 National Defense Authorization Act, into law on December 26, 2013.[5]

In a future IGGI post, I will post materials about federal and state public records acts as a guide for information acquisition about the people’s business.

[1] http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/oct/10/cpi-report-press-freedoms-obama

[2] http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2013/05/21/obama-the-media-and-national-security/only-nixon-harmed-a-free-press-more

[3] http://cpj.org/reports/2013/10/obama-and-the-press-us-leaks-surveillance-post-911.php

[4] http://www.forbes.com/fdc/welcome_mjx.shtml

[5] http://communities.washingtontimes.com/neighborhood/american-millennial/2013/dec/27/breaking-news-michigan-nullifies-ndaas-indefinite-/#ixzz2rX661Dpi

Other References:

Anderson, L.W. (Ed.), Krathwohl, D.R. (Ed.), Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Complete edition). New York: Longman.

Bloom, B. S.; Engelhart, M. D.; Furst, E. J.; Hill, W. H.; Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Image Source: IGGI’s representation of Anderson & Krathwohl (2001) stages of critical thinking. This is a revision of Bloom’s (1956) classic taxonomy on the same subject.